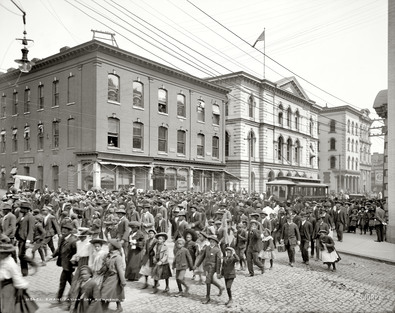

Emancipation Day 1905 - and 'The Strange Career of Jim Crow'

From the Washington Post of April 4, 1905:

From the Washington Post of April 4, 1905:

“Richmond, Va., April 3 -- Thousands of Negroes observed Emancipation Day in Virginia today. The occasion resulted in an outpouring of the race never before equaled, armed with miniature United States flags and attended by brass bands.

"In addition, there was a unique feature to-night, the inauguration of a colored President. At True Reformers' Hall the interior of the White House was reproduced, and all the ceremonies incident to the induction of a Chief Magistrate into office were gone through with.

"Today was also the fortieth anniversary of the evacuation of Richmond by the Confederate forces and the partial destruction of the city by fire.”

This photo puzzled me when I first saw it at the Shorpy Historic Picture Archive. Wouldn’t 1905 have been in the period of peak ‘Jim Crow’ white supremacism, when African Americans lived under harsh repression and the violence of the Ku Klux Klan? How then could thousands of them have been marching festively and peacefully through Richmond – the former capital of the Slave Power - to celebrate the defeat of that very Power forty years before?

C. Vann Woodward’s classic 1955 study ‘The Strange Career of Jim Crow’ shows how much more complicated was the path of African American emancipation than I had imagined. Despite the unremitting efforts of southern white supremacists, it took a long time to deprive African Americans of the political and civil rights they had won during the Reconstruction Era of 1865-77.

C. Vann Woodward’s classic 1955 study ‘The Strange Career of Jim Crow’ shows how much more complicated was the path of African American emancipation than I had imagined. Despite the unremitting efforts of southern white supremacists, it took a long time to deprive African Americans of the political and civil rights they had won during the Reconstruction Era of 1865-77.

According to Vann Woodward, “it would be a mistaken effort to equate this period in racial relations [from the late 1860s into the 1890s] with either the old regime of slavery or with the future rule of Jim Crow. It was too exceptional.”

He cites the experience of an African American newspaperman T. McCants Stewart who traveled through the South in 1885:

“From Columbia, South Carolina, he wrote: ‘I feel about as safe here as in Providence, R.I. I can ride in first-class cars on the railroads and in the streets. I can go into saloons and get refreshments even as in New York. I can stop in and drink a glass of soda and be more politely waited upon than in some parts of New England.’ He also found that ‘Negroes dine with whites in a railroad saloon’ in his native state. He watched a Negro policeman arrest a white man ‘under circumstances requiring coolness, prompt decision, and courage’; and in Charleston he witnessed the review of hundreds of Negro troops.”

African Americans “continued to vote in large numbers in most parts of the South for more than two decades after Reconstruction…. Not only did Negroes continue to vote after Reconstruction, but they continued to hold office as well. Every session of the Virginia General Assembly from 1869 to 1891 contained Negro members. Between 1876 and 1894 North Carolinians elected fifty-two Negroes to the lower house of their state legislature, and between 1878 and 1902 forty-seven Negroes served in the South Carolina General Assembly.”

Vann Woodward explains how the conservative elites who took power in the South after Reconstruction – the so-called ‘Redeemers’ – found it opportune to include African Americans in their political coalitions. The policies of these elites, reflecting the interests of big business, corporations, railroads, and banks, were highly unpopular among the poor, white rural population of the South, who organized in third-party movements to challenge the conservative Democrat elites. “In this situation”, says Vann Woodward, “conservatives were obviously in need of friends, and as the third party grew … the conservatives naturally sought an understanding with the Negroes. … The Negro voters were therefore courted, flattered, ‘mistered,’ and honored by Southern white politicians in the ’eighties as never before.”

Of course, none of this means that this period was any kind of ‘golden age’ in American race relations. “On the contrary, the evidence of race conflict and violence, brutality and exploitation in this very period is overwhelming. It was, after all, in the ’eighties and early ’nineties that lynching attained the most staggering proportions ever reached in the history of that crime. Moreover, the fanatical advocates of racism, whose doctrines of total segregation, disfranchisement, and ostracism eventually triumphed over all opposition and became universal practice in the South, were already at work and already beginning to establish dominance over some phases of Southern life.”

And yet – “The era of stiff conformity and fanatical rigidity that was to come had not yet closed in and shut off all contact between the races, driven the Negroes from all public forums, silenced all white dissenters, put a stop to all rational discussion and exchange of views, and precluded all variety and experiment in types of interracial association. There were still real choices to be made, and alternatives to the course eventually pursued with such single-minded unanimity and unquestioning conformity were still available.”

There were real choices to be made; there were alternatives; there was no ‘historical necessity’ to go down the dark path that was eventually pursued - this is the essential message that Vann Woodward makes repeatedly in this brilliant work, which itself became an influential document in the Civil Rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s.

There were real choices to be made; there were alternatives; there was no ‘historical necessity’ to go down the dark path that was eventually pursued - this is the essential message that Vann Woodward makes repeatedly in this brilliant work, which itself became an influential document in the Civil Rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s.

If something is not a necessity, then it is a contingency – something that could have been otherwise. I can hardly do justice in this post to Vann Woodward’s nuanced, complex discussion of the historical contingencies that led to a “capitulation to racism” in the 1890s and 1900s, a relaxation of the forces that had hitherto kept in check “the elements of fear, jealousy, proscription, hatred, and fanaticism [that] had long been present, as they are present in various degrees of intensity in any society.”

A large part of the story was the long agricultural depression of the 1880s and 1890s, aggravated by cyclical recession in the ‘90s. “A great restiveness seized upon the populace, a more profound upheaval of economic discontent than had ever moved the Southern people before, more profound in its political manifestations than that which shook them in the Great Depression of the 1930’s.”

An unprecedented storm of Populist discontent arose against the big-business policies of the Southern conservative elites, who then had to adjust their political strategy. The Populist movement tried at first to build an alliance of poor whites and blacks, but the elites seized upon its vulnerability, the deeply embedded racism of the white rural poor. To divert and frustrate economic populism, the Southern elites offered up the African American as a scapegoat – the complete disenfranchisement and social segregation of American Americans as the answer to the problems of the white poor.

“The bitter violence and blood-letting recrimination of the campaigns between white conservatives and white radicals in the ’nineties had opened wounds that could not be healed by ordinary political nostrums and free-silver slogans. The only formula powerful enough to accomplish that was the magical formula of white supremacy, applied without stint and without any of the old conservative reservations of paternalism, without deference to any lingering resistance of Northern liberalism, or any fear of further check from a defunct Southern Populism.”

And it was in the late 1890s and the first decade of the 20th century that this veritable counterrevolution was put through. This photo of Emancipation Day, 1905 in Richmond Virginia is thus the picture of a historical turning point and an unfolding tragedy – a last expression of the hopes and freedoms that African Americans had carried forward from the Civil War and the Reconstruction Era, which were even then in the course of being extinguished. It took till the Civil Rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s to knock down the Jim Crow regime set up at the time of this picture. It’s in the complicated aftermath of that movement that we’re now living.